Some Lateral Restructuring Interview Questions and Other Stuff

Updated:It can seem like time in a flat circle and that we’ve somehow landed back to where we were only a few years ago with some tech stocks reaching eye-watering multiples and crypto suddenly hitting new highs again (welcome news for Silver Point, Attestor, Baupost, Canyon, Oaktree, etc. that have aggressively bought up FTX claims – although most, like Oaktree, started snapping up claims in late '23 after it became pretty clear that recoveries would be at or around 100% and the major question just became when those recoveries would flow).

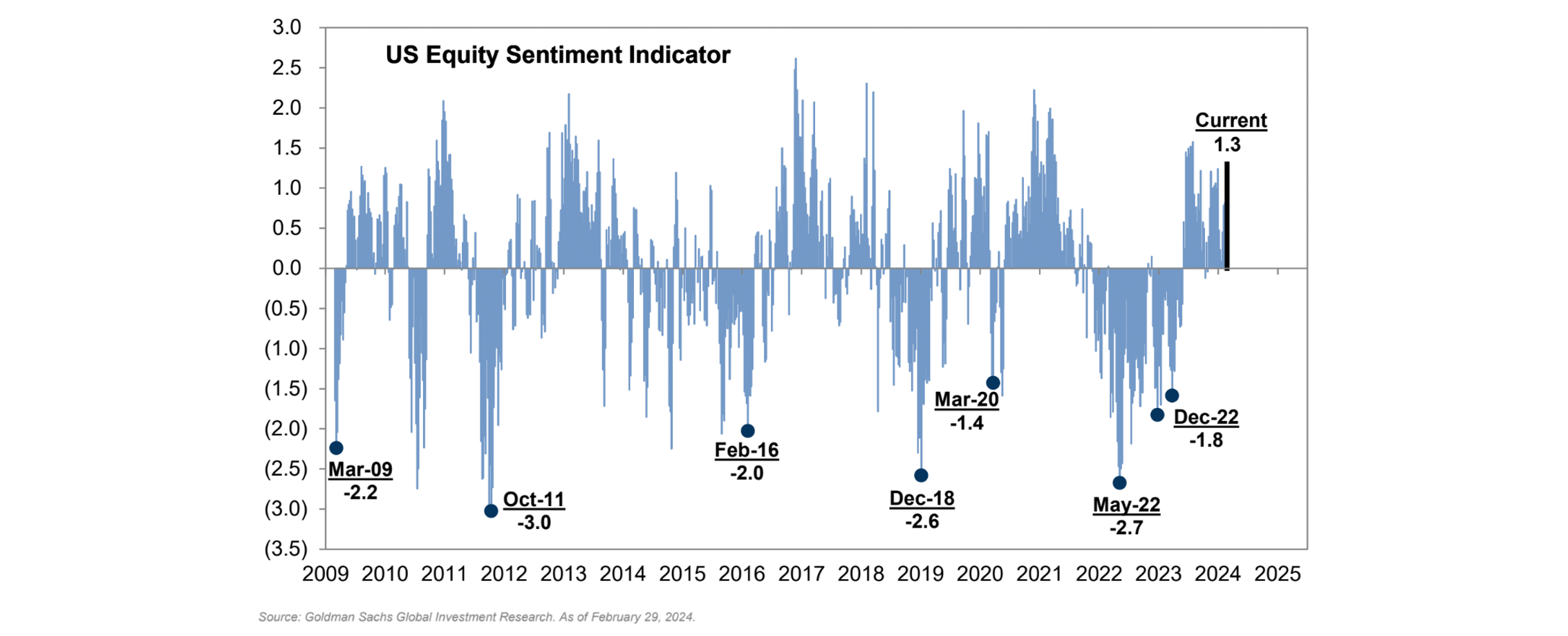

So, as is tradition whenever markets start gaining steam, we've started to see folks dust off their old hot takes about how restructuring activity is about to dry up based on the price action in either equities (bad take) or public credit (better take, but lacks some nuance).

First, in terms of equities, the list of reasons why a connection is tangential at best is too long to litigate here. But suffice to say the kind of froth we’ve seen in equities as of late, even if it continues, won't be a harbinger of less restructuring activity in the future because the current froth (if one believes it is froth) isn’t paired with a low rates environment (or the anticipation of a return to one) as was the case in 2020-22.

There's no getting around the fact that SOFR is still over 500bps, and while this is a net positive for those companies that have little to no debt (but lots of cash on their balance sheets) it’s a net negative for those companies with unhedged floating rate debt or maturities that will need to be refi’ed soon that have been hoping for some reprieve from SOFR’s surge since the Fed’s rate hike campaign began.

And when one looks under the surface at the apparent froth in equity markets this bifurcation is being captured (so maybe equity markets aren't quite as irrational right now as some perpetually pessimistic credit investors would like to suggest). For example, Goldman creates custom indices that lump together equities that have the same characteristics, and if one looks to their “strong balance sheet” index it’s up over 10% YTD and if one looks to their “weak balance sheet” index it’s flat on the year (despite NDX and SPX both being up around 7% YTD).

What we’re seeing in equities isn’t risk-on sentiment pervading all corners – what we’re seeing is companies with light balance sheets and high growth prospects being rewarded due to a belief that we won’t see material economic weakness this year (remember that this time last year a recession occurring sometime in the next year was the consensus view) while those with heavy balance sheets and low growth prospects are still stuck in the mud due to the prevailing rates backdrop.

This bifurcation can also be seen through another Goldman index. This one of CCC-rated credit issuers that can then be compared to SPX. Notice when the meme-mania (that involved quite a few stressed public companies) peaked in '21 and when our current rate hike cycle began to be priced in (the temporary uptick in Q4 '23 was due to the rates market getting ahead of itself and pricing in six rate cuts for '24 before pairing that back to around three now).

Second, in terms of credit, there's no doubt that credit markets have moved in sympathy with equity markets in recent quarters. As should be expected since this time last year a recession within the next year was the consensus view and there was still uncertainty over when the Fed would end its rate hike cycle. Whereas now we've seen above-trend growth over the last year, the Fed is firmly on pause, and trend to above-trend growth over the next year is the current consensus view.

As a result, credit markets are more open than they’ve been in a while, and spreads are extremely tight all things considered. For a sign of how things have changed, look no further than Coinbase announcing plans to offer $1bn of convertible SNs. Here's a little historical overview of where CCC spreads are now (well, as of a few weeks ago) and how much they've tightened in over the last few quarters...

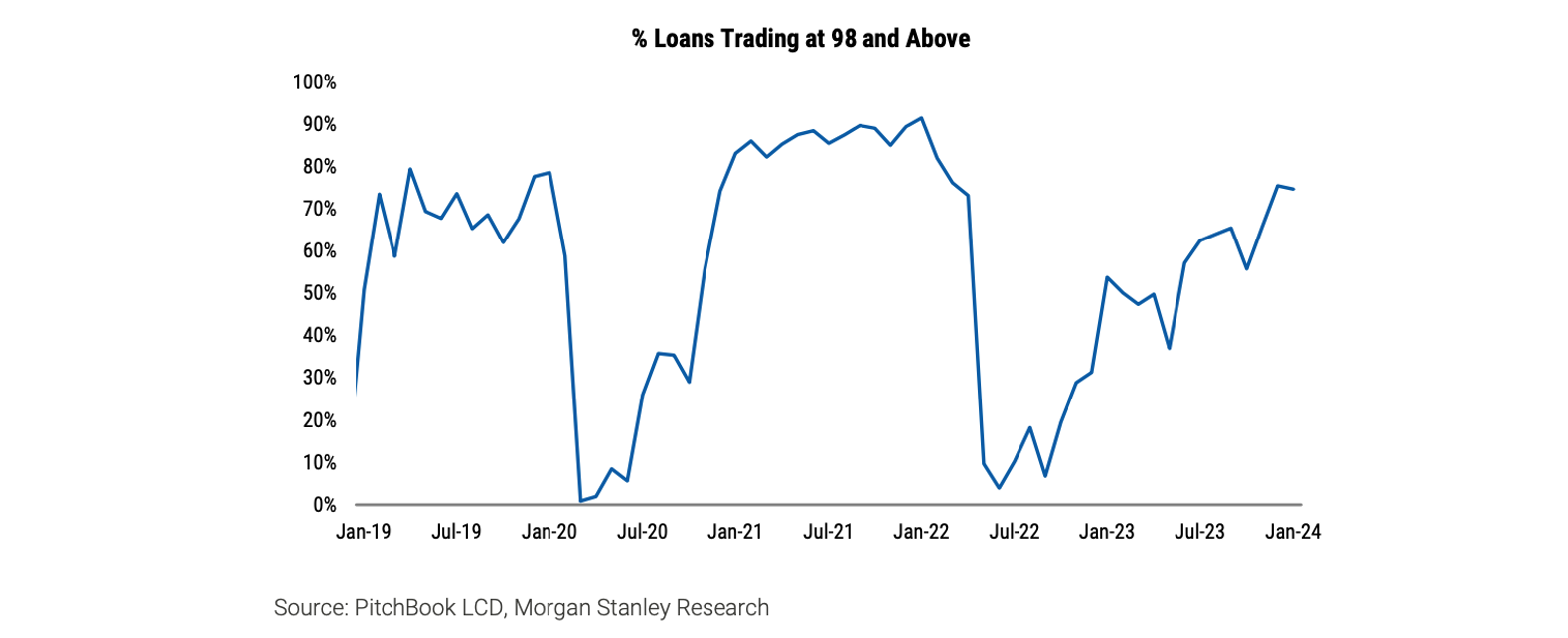

However, the hyperventilation over the decline of spreads, and the subsequent decline in the amount of "distressed" inventory (read: the amount of loans / notes currently trading above a certain spread), vis-à-vis future restructuring activity is all a bit much. Sure, this is a (much) better barometer than equity price action (as mentioned above, that's a low bar to clear) but not by as much as some suggest (especially with the rise of private credit, which many ignore in their prognostications because of the opacity there).

Insofar as loans and notes trade up it can remove some companies, that were at the knife edge, from the pool of those likely to restructure (read: the pathway toward a regular-way refi looks more clear, or at least more doable). However, for those still burning cash and / or with maturities they simply can't refi in our current rates environment, even with tighter spreads and lower yields, their capital structure trading up a bit per se doesn't absolve the need to restructure – it simply informs the kinds of transactions that can be done and / or the economics of those transactions (e.g., an amend-and-extend will be easier and less expensive to do, less discount capture will probably be achieved in an exchange transaction, etc.).

It's perfectly reasonable that some stressed and distressed names have traded up and that the HY primary market has reopened over the last few quarters based on i) the Fed pausing and making it pretty clear that this rate hike cycle has come to a close and ii) the fact that (somehow) the most aggressive rate hike cycle in four decades hasn't spurred a recession and now isn't anticipated to do so.

Because much of the price action we saw over the last few years, along with the more or less frozen nature of credit markets, was driven by deep uncertainty over the future – and this led to some that shouldn't have been stressed or distressed based on their fundamentals trading as such because people basically thought, "Well, if the Fed's rate hike cycle continues even further, or if we suddenly land in a recession, then even though this credit doesn't really look that stressed or distressed based on its fundamentals now, in those situations it could be."

Whereas now, as the dust has settled a bit, the draconian downside cases that led to so many being sucked into stressed or distressed territory have been discarded. So, as a result, those credits that were never really stressed or distressed based on their fundamentals have been pulled out of stressed or distressed territory and, in some cases, have even been able to refi upcoming maturities when they wouldn't have been able to a year ago.

To this end, since Nov '23 we've had issuers that traded at stressed (x > 600bps) or distressed (x > 1000bps) levels last year, but no longer are, raise $36bn of new HY funding (almost all to refi upcoming maturities). And over the last few weeks we've had over $10bn of HY deals minted, likewise almost all to refi upcoming maturities (e.g., Clear Channel, CoreCivic, New Fortress, etc.).

However, even though this credit market reopening has been robust - primarily because there was such a backlog due to the primary market being more or less frozen for a prolonged period for any company that looked pretty stressed - it hasn't been broad. Those that are ~8x levered or more through their capital structure are still more or less frozen out, and likely will be for the foreseeable future as folks have internalized that we may see few (or no) rate cuts this year.

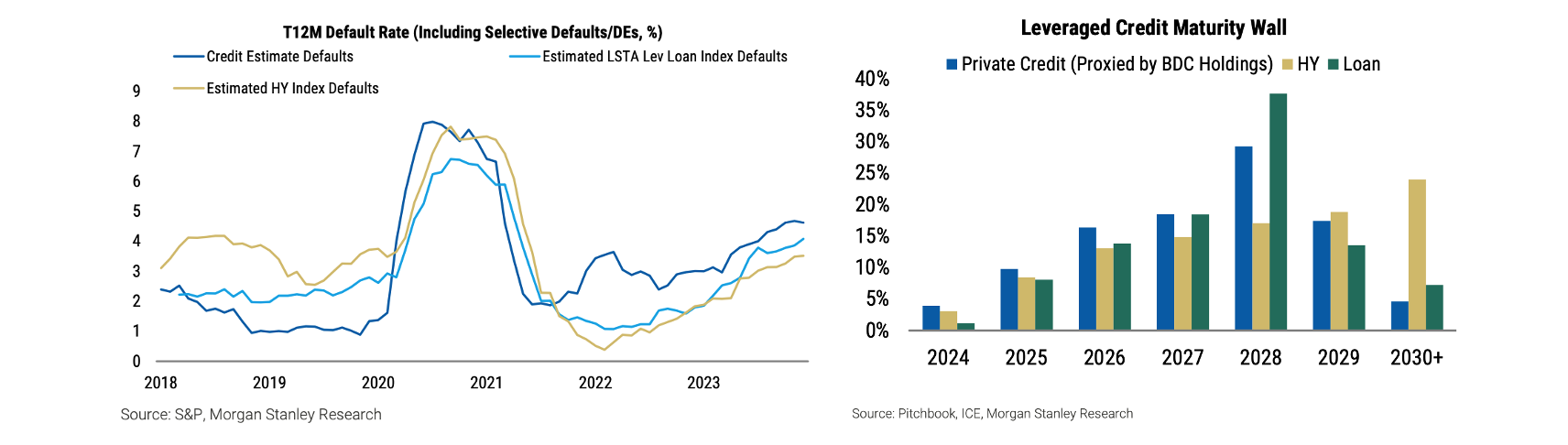

In the end, from a restructuring perspective, as long as rates stay elevated we'll still see plenty of activity as those that have waited with bated breadth for the cut cycle to commence (e.g., lots of sponsor-backed companies) run out of time and are forced to bite the bullet and do something. It’s still all about (base) rates, and right now the rates market is pricing in only around three cuts this year – and there are some, like Torsten Slok at Apollo, that have made the (bold) call in the last few days that we'll have no cuts this year at all.

I'll perhaps save a longer rant for another time. But looking at broad secondary market price action – whether in terms of equities (bad) or public credit (better, kind of) – and making inferences about future restructuring activity sounds sensible enough.

However, one has to be careful about what broad pricing is actually telling you (especially in the midst of a volatile rates environment) and what nuance is displaced when looking at a line chart or a few numbers on a screen that take into account such a wide universe of companies (some of which were never liable to restructure to begin with unless the primary market remained frozen for a prolonged period).

In other words, when you hear about spread tightening across a certain credit rating, or how much distressed inventory has fallen, or see a chart like the one below it's important to not construct a narrative that overinterprets what's really happening. Because, for example, one could construct a narrative based on the chart below that the credit market has turned red hot, that we've closed the chapter on this distressed cycle, and that restructuring activity will probably be much more muted moving forward.

But, in this instance, the real story this chart is telling you is largely one of the hunt for yield that's taken place over the last year as rates have reached their crescendo and the belief among credit investors that, based on the diminished likelihood of a recession happening relative to the consensus this time last year, if one's high enough up in the capital structure then one will be well covered even if a restructuring of some kind occurs (and will be well compensated along the way due to our current rates environment).

So, sure, this chart does signal that we'll probably have less restructuring activity moving forward than one would've thought even a few months ago – but the signal vis-à-vis future restructuring activity isn't as strong as the sharp up-and-to-the-right line would perhaps suggest because it's been driven primarily by the factors mentioned above. In other words, it's not that charts like this have no directional value, it's just that they're prone to overinterpretation as people look at a sharp upward movement in pricing and think there'll be a similarly sharp decline in restructuring activity. But that's not the case here.

Ultimately, even those that are most bullish on credit acknowledge that the default rate probably hasn't peaked quite yet (although some see a peak in 2H 24). Further, those that sound the drumbeat the loudest vis-à-vis calmer restructuring activity in the future based on the price action in public credit tend to outright ignore private credit where everything is famously marked to par until suddenly it isn't – and due to the outsized role of private credit over the last few years, especially vis-à-vis buyouts, that's likely leaving at least half of the story untold.

So, what we've seen over the last few quarters in credit, similar to a certain extent to what we've seen in equities, is a bifurcation develop – one that could deepen, remain stagnant, or reverse itself – where those that were probably unlikely to restructure, but that some might have taken a bit closer of a look at last year due to where their debt happened to trade, now look even less likely to need to restructure.

Whereas the core universe of companies that everyone knows will need to do something at sometime - unless there's a remarkable turnaround in their fundamentals or we see a rapid rate cut cycle commence - remain resigned to the same fate even if their debt has traded up a bit and they've thus contributed to the spread tightening seen in some of the charts above. For this core universe, it's still a matter of when, not if, they take action and what they do – and the longer rates stay higher the more companies that'll be sucked back into this universe.

This is all much different than late-2020 to 2022 where we had a bunch of companies that seemed destined to restructure leverage (actual) hot credit markets driven by zero rates - or even hot equity markets - to avoid having to restructure (at least for a while). We aren't there now, and won't be even if rates normalize a bit over the rest of '24.

Note: If you don't find reading Howard Marks too tedious, I've uploaded his memo from Jan 2024 on rates, credit, misallocation, and what a new normal could, or should, look like.

Note: I wrote all the above last week, but as it happens a few days ago a new episode of Bloomberg's FICC Focus came out that has an interview with Tuck Hardie (MD at HL) that's excellent and worth a listen. He echoed much of the above re: the bifurcation, the impact of rates, how many (especially sponsor-backed) companies are on the sidelines in a vain (?) attempt to withstand the rates storm and deal with their capital structures in a better environment, that we're still very much in a distressed cycle irrespective of how tight credit is right now, etc. Hardie also enters into a nice little rant about how liability management exercises (LMEs) are nothing more than a "new buzzword for out-of-court transactions" which exactly mirrors my (much lengthier) rant about the acronym in the 2023-24 Bonus Guide (where I said it's hard to imagine there's a turn of phrase, or an acronym derived therefrom, that could be more boring, vague, and devoid of explanatory power – why some insist on using it at every possible juncture is beyond me).

I haven’t had much free time over the last few months, so haven’t had the chance to cook up some longer post (e.g., a double-dip debrief or non-consensual third-party release rant). Although, I did carve out some time over the holidays to write a long 2023-24 Bonus Guide with a bunch of interview questions (some that came up in full-time or lateral interviews – then a bunch of more difficult ones that I dreamt up to explain certain concepts). So, here are some of those questions from the 2023-24 Guide...

What’s a J. Crew blocker and has it become common?

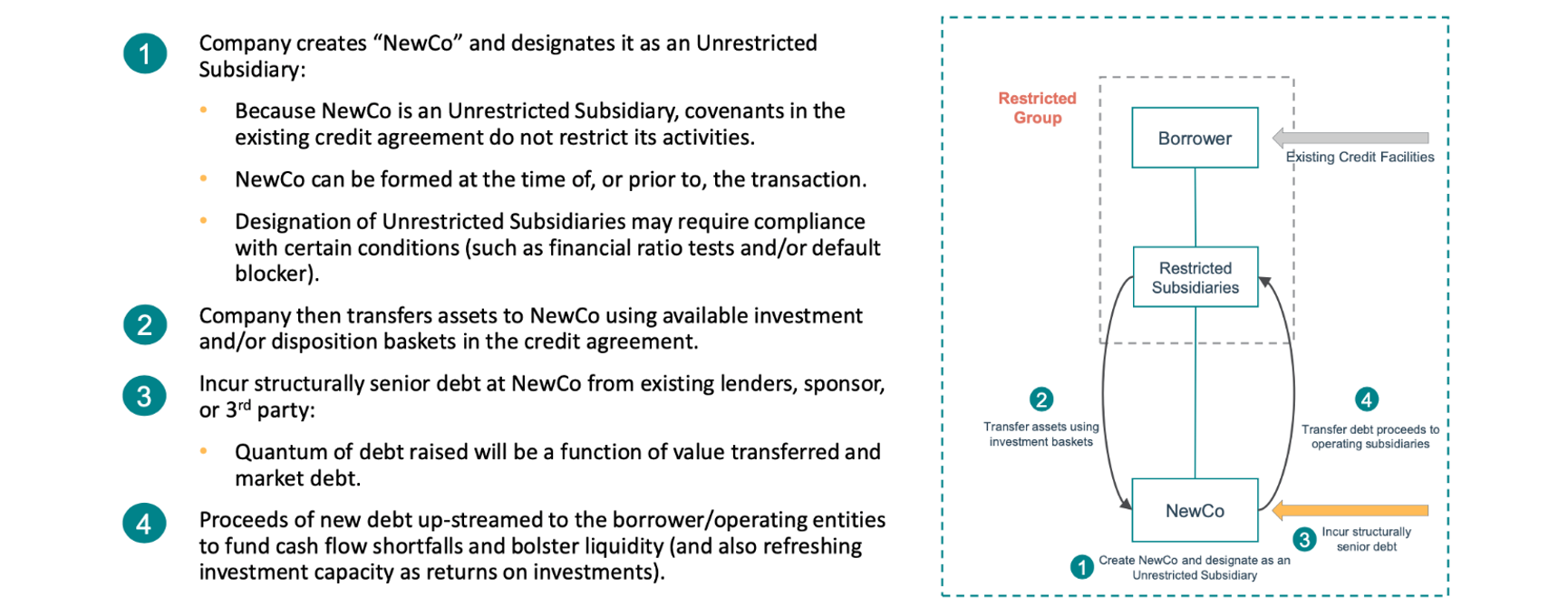

We’ve talked (a lot) about drop-downs vis-à-vis Serta and also a bit vis-à-vis Trinseo in the Double-Dip Guide. Here’s a nice little overview as a refresher...

The reality is that preventing a drop-down, similar to preventing a double-dip, is a bit harder to do than preventing a non-pro rata uptier because the crux of the transaction is utilizing the investment capacity that’s outlined in the debt docs (as I touched on a bit in a postscript within the Serta Postmortem Guide).

I mean, sure, these could be prevented by taking a more sledge hammer approach and providing less investment capacity in the docs at inception – but the company wouldn’t be as interested in this as the investment capacity is critical for other business uses too and would heavily restrict its flexibility (remember that all debt docs are heavily negotiated and a company, all else equal, will opt to go with lenders that are willing to agree to docs that put them in less of a straight-jacket – sometimes even if that results in a slightly higher rate).

Since the “classic” drop-down involved the transferring of intellectual property, and since IP is the crown jewel for many types of companies, the classic J. Crew blocker has been aimed at preventing companies from shifting material IP from the restricted group down to an unrestricted sub (which, if allowed, would then enable the company to incur fresh debt at the unsub and give those new unsub lenders a structurally senior claim on the material IP residing there).

This kind of blocker, to be clear, doesn’t prevent drop-downs from occurring writ large – other material assets could still be transferred down. Rather, it prevents one specific type of drop-down that is (was) most common, especially among retailers where the IP is a critical part of the business (in other words, where the brand really is the business). So, it’s a bit more surgical and something that companies have been more liable to go along with.

There are some different formulations of J. Crew blockers and some are a bit easier to side-skirt than others. But the most traditional basically says, “The Company shall not permit any of its Restricted Subsidiaries to sell, convey, transfer, or otherwise dispose of or license its Material Intellectual Property to any Unrestricted Subsidiary.” (There can also be prohibitions on transferring IP to non-guarantor restricted subs since even though they are bound by the negative covenants of the pre-existing debt docs they don’t guarantee the pre-existing debt, so holders of the non-guarantor restricted sub debt would have a structurally senior claim on the IP located there.)

J. Crew blockers have become more common and are in a majority of new loan deals (read: in most quarters a little over 50% of all deals will have some kind of J. Crew blocker). Although it’s worth mentioning that there’s a bit of selection bias here. The healthiest companies (in other words, those that at issuance are least likely to do a drop-down) or those who are least set up to do a drop-down (in other words, those where IP is less central to the business) are those most liable to include it as the company basically has the attitude of, “Well, lenders seem to care about this, so whatever we’ll make the concession.”

Note: The term “J. Crew blocker” is used as a catchall for drop-down protection of any kind – even if that protection is protecting against transactions that are different than the original J. Crew drop-down (e.g., involving material assets of any kind, not just material IP).

Note: In the past we’ve seen a few J. Crew blocker formulations that prevented restricted subs that held IP from being designated as an unsub but that didn’t otherwise limit the transfer of IP to an unsub. I touched on designation devilry in the Double Dip Guide, so the loophole in this style of blocker might be immediately obvious to you: the company could simply designate a random (empty) restricted sub as unrestricted and then transfer the IP to it after (so, in this case, a restricted sub that held IP would never have technically been designated as unrestricted).

Note: There have been a few credit agreements that have adopted so-called Envision blockers that, like J. Crew blockers, are meant to prevent drop-downs but that take a different approach and are named after a different contentious transaction (Envision) that involved a Frankenstein-esque multi-step drop-down and uptier which I've brought up briefly in earlier posts. These blockers seek to limit the dollar amount of assets, not the type of assets, that can be transferred to an unrestricted subsidiary, and this is often accomplished through only allowing the company to tap the dedicated “investments in unrestricted subsidiaries” basket as opposed to tapping all the broader set of investment baskets (e.g., investments in unrestricted subsidiaries basket + general investments basket + leverage-based investments basket, etc.) in the docs to effectuate an unsub transfer. Although, in case it's not already clear, this is all well beyond what you need to know.

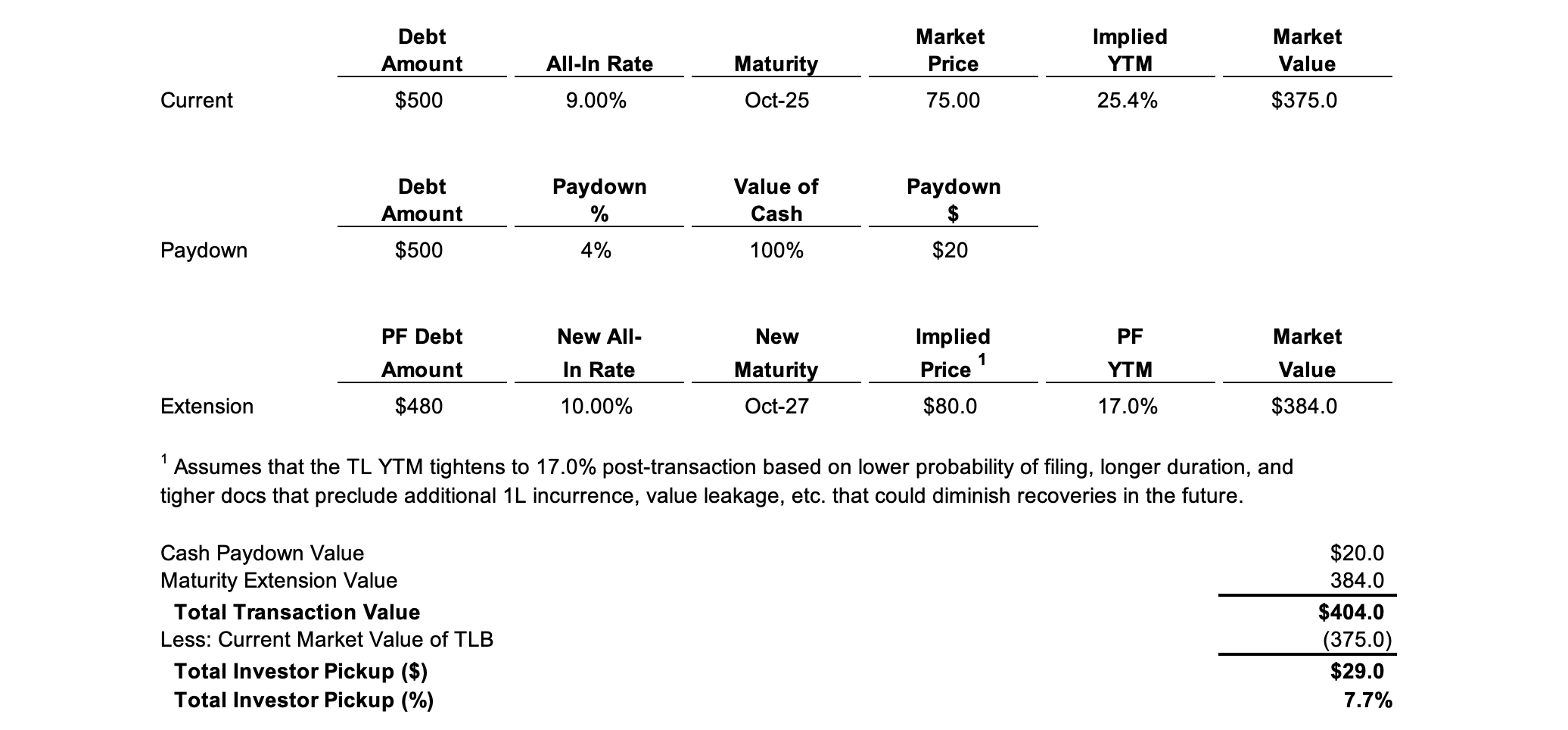

Let’s imagine that XYZ Inc. has a Term Loan that’s trading around 75 with a YTM of around 25%. Right now we’re mulling over a little amend and extend that would involve XYZ using cash on the balance sheet to paydown 4% of the TL at par, enhance the TL’s economics by 100bps to S + 500bps, and tighten up the credit agreement (e.g., decrease additional 1L incurrence, add J. Crew and Serta blockers, etc.). All in return for the TL maturity being bumped out a few years. If we believe that as a result of this transaction the TL’s YTM will tighten to 17.0% – implying a post-transaction price of around 80 – how could we think about a TL holder’s “return” from the transaction?

So, here we’re thinking that if the transaction occurs the YTM will tighten (fall) a bit because we pushed out a maturity and, if we assume the company’s FCF situation doesn’t become too dire, the probability of filing has been lowered. Plus, if we assume the credit agreement was pretty loose beforehand, through tightening up the credit agreement the possibility has been diminished that the company will do something that could eviscerate the position / recovery of the pre-existing holders through a more creative transaction (e.g., a non-pro rata uptier or drop-down) or just threaten their recovery through lots of additional 1L incurrence that would reside pari to them (so, this doc tightening would be a net positive for pricing as it reduces downside risk to holders).

Needless to say, the pro-forma YTM is a guesstimate and you’d want to look at how the transaction would look at various pro-forma levels (e.g., 16%, 18%, 20%, etc.). However, if we assume that the YTM will tighten to 17%, and that the TL trades at 80 after the transaction, we can figure out what the immediate “return” would look for holders (of course, most will have bought the TL at much higher levels so it’s not like their real return will suddenly be positive by dint of the transaction – the “return” here should be thought of as what a holder has “made” as a direct consequence of the transaction being done).

So, first, we know pre-transaction that there’s $500mm of the TL outstanding and it’s trading at 75. Therefore, the market value of the TL is $375mm. Second, we know holders will receive their pro-rata share of a 4% paydown of the face value of the TL, in cash, that amounts to $20mm in total ($500mm * 0.04). Third, we know the new market value of the TL will be the pro-forma amount of debt ($480mm due to the $20mm paydown) and we’ve been told that the TL will trade around 80 post-transaction based on a pro-forma YTM of 17%. Therefore, if we assume the TL will trade at 80 then the market value of the TL will be $384mm (higher than before, even with the lower face value amount!).

So, we can think about the return to holders as being the $20mm in cash plus the new market value of the debt that they still hold minus the current market value of the TL, or $20mm + $384mm - $375mm = $29mm. Thus implying an investor pickup (return) of around 7.7% ($29mm / $375mm) due to the transaction.

Note: This will probably never be asked, but if it is then the interviewer will throw out round numbers or want a rough approximations for the return to keep the mental math gymnastics to a minimum. In the real world, the numbers will all be a bit messier but in the below I chose dates such that the implied trading price based off the round YTM (17%) will also be a round number (80). (In the Bonus 2023-24 Guide I used a more real-world example where the current market price is a touch below 75 and the implied trading price, if we assume a YTM of exactly 17%, is a touch below 80 too – I’ll probably change it to use rounder numbers to avoid confusion, but it's all the same approach).

Let’s imagine that ABC Inc. has a HoldCo that’s issued $100mm of Senior Notes and holds 100% of OpCo1’s equity and 100% of OpCo2’s equity. Further, let’s imagine that HoldCo sent part of the proceeds from the Senior Notes to OpCo1 in the form of a $40mm (unsecured) intercompany loan and, in return, received an intercompany loan receivable. Today, HoldCo has no other assets beyond OpCo1 equity, OpCo2 equity, and the intercompany loan receivable; OpCo1 has an EV of $50mm, Senior Secured Notes of $30mm, and Senior Notes of $10mm; and OpCo2 has an EV of $80mm, Senior Secured Notes of $40mm, and Senior Notes of $20mm. Given all this, what are the recoveries here assuming that there are no guarantees?

So, since we know that the recovery of HoldCo’s SNs will probably be influenced by the residual equity value flowing from one of the OpCos, let’s start with one of them. For OpCo1, we have an EV of $50mm and, after dealing with the $30mm of SSNs that’ll receive full (100%) recovery, we have $20mm in distributable value left against $50mm of unsecured claims (the $10mm of SNs and the unsecured $40mm intercompany loan). Therefore, the recovery for both will be 40% or $4mm for the SNs and $16mm for the intercompany loan. And, of course, there’ll be no residual equity value that’ll flow to HoldCo.

For OpCo2, we have an EV of $80mm and that more than covers both the $40mm of SSNs and the $20mm of SNs, so both receive a 100% recovery. This leaves $20mm of value that’ll then flow to HoldCo since HoldCo holds 100% of OpCo2’s equity.

Given this, if we think about HoldCo there are $100mm of SNs outstanding and two sources of value: the $20mm from OpCo2, and the $16mm from the intercompany loan. Since remember that the intercompany loan was made from HoldCo to the benefit of OpCo1 – so the recovery of the intercompany loan we determined in OpCo1’s waterfall is recovery that “belongs” to HoldCo, and we haven’t yet determined what creditors will benefit from this intercompany loan recovery. So, the waterfall at HoldCo is straight-forward: there are $100mm of SNs and there’s $36mm of distributable value, so HoldCo’s SNs will receive a 36% recovery.

Put another way, if we think about HoldCo it has $100mm of liabilities (the SNs) and three assets: 100% of OpCo1 equity (that we’ve determined is worth $0mm), 100% of OpCo2 equity (that we’ve determined is worth $20mm), and a $40mm intercompany loan receivable (that we’ve determined is worth $16mm). Therefore, we have $36mm in value against $100mm of claims, thus the 36% recovery for HoldCo’s Senior Notes.

Note: This kind of question hasn’t been asked before (although EVR asks a similar one sans the intercompany loan component). But I figured I’d add it since it’s a simpler interview-style waterfall question that involves an intercompany loan receivable relative to the (real-world) waterfall involving an intercompany loan receivable that I went through in the Double-Dip Guide vis-à-vis Wheel Pros that’s a bit more complicated.

Postscript

I’ve talked a lot over the last few months about Serta’s saga and the chill that the Fifth Circuit appeal has cast over these kinds of transactions. This has only been compounded by the travails of Incora, who filed back in June of 2023, and their adversary proceeding which has turned into a bit of a mess (I talked about Incora’s aggressive non-pro rata uptier a few times back in 2022 and 2023 before they bit the bullet and filed).

For a time, in the halcyon days of mid-2023, it looked like non-pro rata uptiers would be rubberstamped and that there wouldn’t be an attempt to unscramble the decidedly scrambled egg that these transactions represent. In fact, the perception that these kinds of transactions would be rubberstamped in-court, after Serta seemed to be well on track, was by in large why Incora filed when and where they did (although they’d be loath to admit it for obvious reasons).

It’s no secret about my views on all of this, so I won’t inject a defense of these transactions here. But the mood does appear to have shifted over these last few months, and the aforementioned Incora adversary proceeding may have more of a gloss of legitimacy than if Judge Jones was at the helm but it's also stretched on and on and on. (Remember we’ve moved from Judge Jones overseeing all of this – for reasons we’ve discussed before vis-à-vis his, uh, undisclosed living situation – to Judge Isgur who has made his views from the bench much less clear to most ears.)

To this end, a little over a week ago we had hearings in Incora’s adversary trial with testimony from a number of those involved in the transaction. I won’t invoke any names here, and I won’t talk about the specifics too much. But in a bizarre exchange we saw Judge Isgur raise his “concern” over possible inconsistencies between what was said on the stand by an advisor to Silver Point and PIMCO and his earlier deposition. This advisor said on the stand that he was aware that a minority group of holders were negotiating with Incora at the same time as Silver Point, et al. but was unaware of the specifics of their proposal on a certain date before the transaction occurred. This mirrored what he said in his deposition.

But then he was shown an email from an MD at Silver Point. This MD told his Silver Point colleagues that their “advisors” had learned the specifics of the minority group proposal (well, that it would involve a drop-down and then some extremely rough numbers).

It was never specified who the advisors were, nor would anyone reasonably think that real proposal specifics were provided from what was described in the email (although actual specifics around the majority group proposal were already pretty well publicized at this time – and, once again, how the minority group learned of the majority approach to begin with, which set off the chain of events I talked about back in 2022, was through a Debtwire article).

In light of this email, the advisor was pressed on the stand about whether he knew of the specifics outlined in the email (he wasn't a recipient of it). Then he was asked if he told the truth in his deposition, despite there being no proof to the contrary, to which the advisor said he did. This led to a bit of back and forth before we had Judge Isgur say, when a lawyer objected to a follow-on question, “That is not an objection. I heard the witness’s testimony today, and I think it’s totally inconsistent with what I’m seeing here. So, I’m very concerned about what we’re hearing. We’re going to let him continue to answer questions.”

This whole line of questioning should be much ado about nothing, but it’s troubling by dint of being treated as a bit ado about something. What the advisor said is that he didn’t know when he became aware of the general concept of the drop-down that the minority group was mulling over, but that he did know about the concept – because of course he did. Everyone knew a drop-down was a viable (albeit inferior) option for Incora, and one that a minority group could opt for in response to the non-pro rata uptier pitch of the majority group.

Knowledge of the specifics never mattered and wasn't determinative. Anyone with access to the docs (read: an advisor to the majority group) could envision what the rough contours of a drop-down proposed by the minority group would look like or at least put an upper bound on it to ensure that the majority proposal was more enticing – as it was, and it wasn't too close.

Anyway, I don’t want to start a rant about the cross-examination, as this isn’t the place to do it. But it does seem like the worst arguments, and the most tangential of tangential issues, are getting the most airtime in Incora. And it does seem that how this transaction came together could inform, whether explicitly acknowledged or not by Judge Isgur, the permissibly of it (something Judge Jones refused to contemplate and which I defended him on despite all his cringe-inducing talk about "financial titans" that engage in "winner-take-all" battles).

The whole situation last week was bizarre, and made all the more bizarre by the specific elements of the transaction that were focused on. For example, there were frequent, torturous discursions into the rationale for the springer when the answer is self-evident. Likewise, lawyers treated it as a bit of a "gotcha" that Silver Point, et al. wouldn't do the same transaction, on the same terms, if it were pro-rata – because of course they wouldn't, that'd be a fundamentally different transaction. Anyway, I'll just say that I admire the restraint (read: self-control) of the witnesses involved and leave it at that.

With all that said, even with all this litigation and the somewhat unfavorable climate for these transactions, we’ve seen a few more uptiers (that we can call quasi-pro-rata, I suppose) either be consummated or kind of unravel over the last few months – desperate times calls for desperate measures.

First, there’s Robershaw which, uh, is a complete and unmitigated mess. So, let's do a quick and dirty overview of what happened (I'll link all the complaints below if you want to read all about it). At first blush, the fact that Robertshaw is such a mess could seem a bit surprising because there weren’t a bunch of neophytes involved here – we had Invesco and Eaton Vance back together again, as they were in Serta, joined this time around by Canyon and Bain.

The transaction itself was simple enough. Robertshaw was bought out by One Rock for $900mm in 2018 and had a $50mm ABL, $510mm 1L, and $110mm 2L. In May of 2023 – around the time that Incora filed – the company faced liquidity constraints and EBITDA was imploding (down a smidge at -74% YoY in Q4 2022).

So, Invesco, Eaton Vance, Canyon, and Bain – that held, in total, 76% of the 1L and 59% of the 2L – completed an uptier that had them invest $95mm of new money into a new First-Out Term Loan; exchange $370mm of their 1L TL, at par, into a new Second-Out Term Loan; and exchange $65mm of their 2L TL, at par, into a new Third-Out Term Loan.

Then, having learnt the lesson of Serta, they decided to be equanimous and offer non-participating lenders the opportunity to exchange their holdings into a mix of Second- and Third- and Fourth- and Fifth-Out TLs (but, of course, in exchange for this equanimity they asked these holders to do them the small favor of not litigating the transaction – although some non-participating lenders still sued, so truly no good deed goes unpunished).

Anyway, this is all is pretty textbook stuff, and if this were where the story ended it'd hardly be worth bringing up. However, a few months after the transaction closed an inglorious series of (absurd) events took place.

The impetus for the circus that would ensue was Invesco, in the near immediate aftermath of the transaction, beginning to buy up, in the secondary market, a simple majority of the First-Out Term Loan and Second-Out Term Loan (in the end, before the brouhaha all began, Invesco had $73.8mm of the First-Out Term Loan, $183.2mm of the Second-Out Term Loan, and $59.2mm of the Third-Out Term Loan).

This was all done on a hush-hush basis, and Canyon, Bain, and Eaton Vance were late to realize that the four firms weren’t all more or less bound together in the capital structure – but instead that Invesco, through now having this simple majority, was alone in the driver’s seat and that the returns of Canyon, Bain, and Eaton Vance were at risk.

This is because through holding a simple majority across the First- and Second-Out, this then allowed Invesco to amend (most of) the terms within the applicable credit agreement and, for all intents and purposes, control the future of Robertshaw unless there was some turnaround in the business that made them no longer need to rely on lenders for support (in other words, if waivers, additional capital, etc. were needed by the company then Invesco was now able to, for all intents and purposes, dictate terms irrespective of what Canyon, Bain, or Eaton Vance thought).

But, as Invesco knew with near certainty, there would be no turnaround in the business: so, in Nov of 2023 after an event of default that Invesco maybe, kind of, sort of forced to happen Invesco, Robertshaw, and One Rock agreed to the contours of a pre-pack (the degree to which they agreed depends on who you believe) that’d have Invesco provide the DIP and stalking horse bid when they filed in Jan of 2024 (read: Invesco would parlay their uptier participation, and secondary market purchases, to own Robertshaw post-reorg through credit bidding the eventual DIP, ABL, and First-Out Term Loan).

But then Robertshaw and One Rock – after having engaged in some level of negotiations over what an eventual filing would look like with Invesco – went to Bain, Canyon, and Eaton Vance to save themselves from having to file (I'm being a bit tongue in cheek here as the fact they’d have to file was all but certain – it was more about which creditors would drive the in-court process and how One Rock could preserve some kind of upside, although that's saying the quiet part out loud).

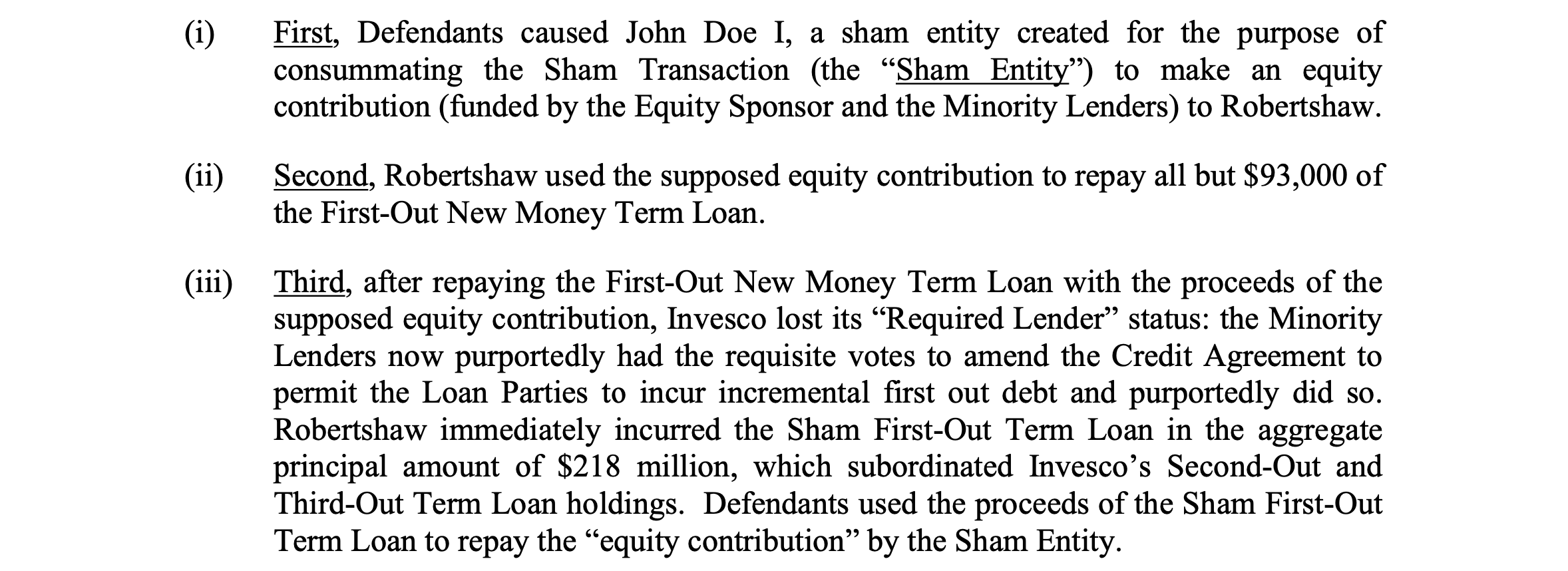

Recognizing that they needed to land back in the driver’s seat – and that to do so would require kicking Invesco out of it – Canyon, Bain, Eaton Vance, and someone else I'll mention in a minute provided $228mm of new money to a newly spun up entity that wasn't technically a Robertshaw subsidiary and thus not bound by the negative covenants under the pre-existing debt docs. This $228mm was then immediately sent from this newly spun up entity to Robertshaw who used it, in part, to take out (prepay) almost all the pre-existing First-Out TL (inclusive of Invesco's entire stake).

It was expensive to take out the First-Out TL with the make whole, but desperate times call for desperate measures and this did result in Bain, Canyon, and Eaton Vance getting back in the driver’s seat that Invesco previously enjoyed alone due to this group now possessing a simple majority (50.05%) across the small stub of First-Out TL left ($93,000) and the Second-Out TL. This then (depending on your perspective) allowed this new simple majority to amend the credit agreement and incur – wait for it – $228mm in incremental First-Out, and a bit of Second-Out, debt the proceeds of which were used to prepay (take out) the $228mm at the aforementioned newly spun up entity.

So, this was all a bit of musical chairs with the end result being that Invesco was out of the driver's seat and there was now $228mm of new First- and Second-Out TLs. (This is a quick and dirty overview, for the step-by-step mechanics, inclusive of how all the proceeds of this $228mm were used, see the adversary complaint linked later. Here's Invesco's shorter summary...)

Invesco wasn’t too pleased about any of this (it’d be one thing if they only held the First-Out and were taken out of the capital structure as that’d still net them a nice IRR for a few months of work, as they did receive $92mm for their $74mm of First-Out TL – but they still held a non-trivial amount of other parts of the capital structure, plus were obviously going to lose out on getting post-reorg control of the company). So, of course, they sued in state court over the “sham” transaction in Dec 2023 (say a prayer for those that had to deal with this over the holidays…).

Note: I’ve joked before that lawyers secretly love writing these complaints because it provides them full license to show off their literary flare and let loose their existential angst against the world – and this complaint was no different. Here are the alleged consequences if Canyon, Bain, and Eaton Vance are allowed to get away with all this: “...there will be no limit to the sophistry and deceit that will infect the distressed debt market for syndicated secured loans. No amount of thoughtfully negotiated credit agreement covenants can ever effectively prevent other transaction parties from nefariously circumventing contractual rights to garner the controlling votes in credit facilities.” This can seem a bit like the pot calling the kettle black, but I'm pretty sympathetic to Invesco on this here.

Now, one might think all of this rearrangement of the deck chairs on the Titanic kind of makes sense from the company’s perspective if they felt that they were being strong-armed into filing by Invesco (as, let’s be honest, they very much were) and if the end result of all of this rearrangement was that Canyon, Bain, and Eaton Vance became reliable partners in the company's capital structure (working together, hand-in-hand to side-skirt filing and enabling the company to grow into their new capital structure.).

But, uh, around two months after Invesco sued over the transaction Robertshaw filed (in the Southern District of Texas, of course, because SDTX still offers debtors the best shot to have contentious uptiers rubberstamped even if Judge Jones isn’t around anymore). And their current RSA contemplates the sale of their assets to Canyon, Bain, and Eaton Vance through a credit bid. So, it’s more or less the exact same concept that Invesco envisioned in their contemplated Jan 2024 pre-pack – but instead of Invesco credit bidding, we have the rest of the original uptier group doing so.

However, in the above I omitted one little detail: that One Rock participated in the December 2023 Bain, Canyon, and Eaton Vance transaction (to the tune of providing ~$42mm of the aforementioned ~$228mm at the newly spun up entity, which transformed into $32mm of the First-Out TL and $10mm of the Second-Out TL), and will credit bid its new claims alongside the other three. So, the rearrangement of the deck chairs may have not made a difference to the company's prospects, which were more or less set in stone back in late-2023, but if this second transaction stands then it'll have made a big difference to the sponsor's returns. And, in the end, isn't that all that really matters?

Note: Robertshaw is a mess, and to be honest there’s no lessons to be learned from it right now (at least not lessons that should be learned). No one covered themselves in glory here although I don't see an issue with Invesco’s approach (albeit a bit of bad sportsmanship involved) and I'm generally sympathetic to (most of) their position on the “sham” transaction – the Canyon, et al. transaction does seem a bit too clever by half, and would be easier to unwind without touching the uptier issue, although if it stands then it would provide another interesting tool in the tool box...

Note: For the other side of the coin, see the initial complaint in the adversary proceeding after Robershaw filed where Robershaw, One Rock, Bain, Canyon, and Eaton Vance make their case. You have to admire them basically saying, "For the life of us, we can't figure out the issue here. Invesco earned a nice return on their First-Out TL, and then they turned around and sued us. All we did was what the credit agreement allowed us to do, no different than what we did with Invesco in the original uptier. Not sure what all the complaining is about. We just operated within the bounds of what the docs allowed."

Second, in less contentious news, there’s Apex Tools (PJT debtor-side, PWP with an ad hoc group of lenders) that did a nice little quasi-pro-rata (everyone can participate but not on the same terms) transaction a few weeks ago. It was all traditional and most of those that could participate on the inferior terms did do so – although, of course, Robertshaw’s transaction was traditional too until Invesco decided to venture off on its own and the comedy of errors discussed above began to unfold.