Upstream and Downstream Guarantees: Definitions and Examples

Updated:Something I’ve written about many times is that when it comes to restructuring, things mean what they’re defined to mean -- not what you think they ought to mean.

For example, if I were to ask you whether or not - in a chapter 11 case - you’d expect second lien noteholders to receive a higher recovery than third lien noteholders you may scoff, tut-tut, and say that obviously this would be the case. First comes after second, second comes after third, etc.

However, things mean what they’re defined to mean, and this obviously holds even more true when it comes to actual tranches of debt. Second lien notes, third lien notes, unsecured notes -- they’re all just labels. While you can safely assume a second lien note probably has a second lien on something, without digging into the credit docs you can’t say much more than that.

In the case of Neiman Marcus, their labeling of their 2L notes and 3L notes was directionally correct but didn’t tell the full story. As it turns out, the 3L notes had, as you’d expect, a third lien on many different things but also had a first lien on some real estate assets that pushed their recovery value above the 2Ls in their initially proposed Plan of Reorganization.

Note: While the initial PoR contemplated the 3Ls likely getting a higher recovery, this was before including 2L consideration coming from the non-debtor MyTheresa. But in order to avoid triggering myself with discussions of retail restructurings during the depths of the pandemic, I won’t open that whole can of worms.

Here's another more common scenario that illustrates this point: sometimes you’ll quickly look at a company and see that they have a few different tranches of unsecured notes. However, you’ll then notice that one tranche has a coupon of 6.5% trading at 95, and another has a coupon of 8.5% trading at 70.

A good interview question would involve asking what explains this discrepancy -- after all, not only could you buy one of these similar sounding tranches cheaper, but it also would give you a better coupon!

If you’ve already read the post I did on structural subordination - or read the dedicated structural subordination guide in the members area - then the answer should be obvious right away: the 6.5% unsecured notes must reside at the OpCo level, where the assets reside, while the 8.5% unsecured notes must reside at the HoldCo level. Further, there must not be an upstream guarantee in place giving the HoldCo notes a general unsecured claim at the OpCo level (because if there were then the HoldCo-level notes would effectively be pari with the OpCo-level notes in terms of priority and thus should be trading at roughly similar levels after adjusting for the modest coupon differential).

Upstream and Downstream Guarantees

Since this is a bit of a longer post, you can use the links below to navigate to each section. Given that we've previously gone through upstream guarantee questions in the structural subordination post, the way I'll try to approach talking about upstream and downstream guarantees this time is primarily through a little hypothetical case (which hopefully helps flesh things out without being too confusing!).

What is an Upstream Guarantee?

What is a Downstream Guarantee?

What is an Upstream Guarantee?

Upstream guarantees are guarantees that are extended by subsidiaries to the parent-level in order to overcome the issue of structural subordination (by giving creditors at the parent-level some form of claim at the subsidiary that has extended the guarantee).

Since this may seem like a bit of an academic definition, let’s clean it up a bit and talk about why upstream guarantees are utilized at all by going through a little hypothetical case.

Let’s imagine that we’re thinking about starting a company in the offshore drilling business. We know that offshore drilling is ever so slightly capital intensive with offshore rigs/drillships costing hundreds of millions of dollars, requiring millions in annual maintenance expense, etc. Further, we know that offshore rigs aren’t exactly commoditized: each is unique in its size, capacity, age, and, most importantly, in its average contractual dayrate.

Another thing we know is there have been many offshore drilling chapter 11 filings over the past few years like Pacific Drilling, Diamond Offshore, Valaris, and Noble. But this reality leaves us entirely undeterred. Despite the fact that we don’t know anything about the mechanics of offshore drilling, we figure that’s entirely inconsequential if only we can craft a perfectly contoured capital structure.

While this latter point is (obviously) written in jest, poor business performance in conjunction with unruly and nonsensical capital structures were the primary drivers of many of the offshore drilling filings we’ve seen over the past few years. It’s not that a perfectly contoured capital structure would have prevented these filing from ever occurring, but they would have provided at least a bit of optionality by leaving the door open to doing clever out-of-court restructurings or finding ways to issue incremental debt.

So, here’s how we’re going to design our hypothetical corporate and capital structure…

If we think about our business conceptually, it’s more or less just a collection of unique offshore drill rigs that are each very expensive and that each throw off a stream of cash flows (assuming they're currently operating). So, what we’re going to do is create a corporate structure that will place each rig into its own OpCo and then establish a HoldCo that will hold 100% of the equity of each one of these operating companies. Here's a little visualization:

What we’re then going to do is issue Secured Notes at each one of these operating companies. The reason for doing so is two-fold. First, we know that credit investors want to have debt housed as close as possible to where the assets of a company actually reside. So, issuing Secured Notes at the operating company (subsidiary) level gives them exactly that. Second, we know each rig is unique and that many credit investors will prefer to be able to get exposure to individual rigs, based on their own analysis and valuation methods, as opposed to getting exposure to all of them lumped together. Remember, these rigs are worth hundreds of millions and produce hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue a day when operating -- in other words, each is really a non-trivial business in its own right.

Now that we have Secured Notes placed at each of our operating company, the question then becomes what to do (if anything) at the HoldCo level. While in this hypothetical example there are no tangible assets at the HoldCo, they do hold the equity of all of our operating companies which certainly does have value assuming the operating subsidiaries aren't underwater (no pun intended).

So, what we’ll do is issue two large tranches of Unsecured Notes out of the HoldCo. Since both of these tranches of Unsecured Notes will be removed from where the assets reside, we’ll need to provide holders a higher interest rate relative to what the Secured Notes are getting. However, insofar as folks believe that there will be sufficient equity value within the operating subsidiaries - that wholly belongs to HoldCo - then the enhanced yield could be quite enticing to those with a slightly greater risk appetite.

More specifically, the first tranche of Unsecured Notes we’ll issue - that we’ll call the Priority Senior Notes - will have upstream guarantees from all the operating companies which will give the Priority Senior Notes a general unsecured claim at each of them. The second tranche of Unsecured Notes – that we’ll just call the Senior Notes – will have no upstream guarantee from any of the operating companies.

From a recovery perspective, this would mean that value from any given operating company will flow first to their specific Secured Notes, then to the Priority Senior Notes due to the upstream guarantee in place, and then to the Senior Notes (as any value left over at an OpCo would flow to the HoldCo given that it holds 100% of each OpCo’s equity). So, even though HoldCo has issued two tranches of unsecured notes, one tranche is structurally senior due to the upstream guarantees they have from the subsidiaries.

What’s described above is really just a heavily simplified and stylized version of Transocean’s corporate and capital structure. First, they have secured notes that are issued at each rig’s specific OpCo with these secured notes being secured by all the assets and earnings associated with that specific rig. Second, they have tranches of unsecured notes at the HoldCo level with varying levels of upstream guarantees (or none at all). Practically, this means that some of Transocean’s HoldCo unsecured notes are structurally subordinate to other HoldCo unsecured notes.

While Transocean hasn’t filed yet, they did do a contentious out-of-court exchange in late 2020 which invited a lawsuit from Whitebox and PIMCO who believed that Transocean stripped their unsecured notes - which were called Priority Guaranteed Notes - of their structurally senior status because the exchange involved the issuance of new unsecured notes - which were called Senior Priority Guaranteed Notes or SPGNs - that had a higher priority than the Priority Guaranteed Notes.

Circling back to what I wrote in the preamble, this is why you can never rely on labels as being overly informative! Here we have some Priority Guaranteed Notes that were subordinated by Senior Priority Guaranteed Notes.

Note: As you can imagine, everything is a touch more complicated in practice. The new SPGNs had a guarantee from three holding company subsidiaries that each, in turn, wholly own certain operating companies. Importantly, when you hear “holding company” that doesn’t necessarily mean the parent-level holding company (e.g., for Transocean, that would be Transocean Ltd.). As Moody’s put in when they first assigned a rating to the new SPGNs, “The SPGNs are structurally subordinated to the outstanding secured [rig-level] debt and the company's undrawn $1.3 billion secured revolving credit facility. The SPGNs are senior to the previously issued PGNs and the senior unsecured notes, and have a priority claim, because of the guarantees from Transocean's Structurally Senior Guarantors, effectively giving these notes a priority claim to the assets held by Transocean's operating and other subsidiaries compared to Transocean's PGNs and senior unsecured notes.”

Note: Technically Transocean Inc. has issued all the unsecured notes and Transocean Ltd. (the true parent-level HoldCo) has guaranteed them. However, Transocean Inc. is the direct and wholly owned subsidiary of Transocean Ltd. So, to avoid splitting the most microscopic of hairs, we'll call the issuer of the unsecured notes, Transocean Inc., the effective HoldCo for our purposes here.

Upstream Guarantee Example

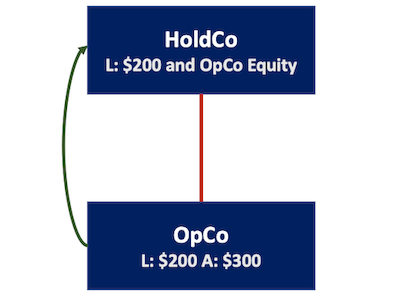

Let’s imagine that we have a simplified little HoldCo / OpCo structure. The OpCo has $300 in assets and has issued $200 in unsecured notes, while the HoldCo has issued $200 in unsecured notes and holds the equity of OpCo. What will be the recovery values with and without an upstream guarantee being in place?

You can visualize the structure as follows -- keep in mind that the HoldCo should always be drawn on top and that any upstream guarantee should be drawn from the OpCo coming up to the HoldCo.

If there’s no upstream guarantee in place, from a recovery value perspective the OpCo unsecured notes would be made whole as they’re fully covered by the assets at OpCo. The $100 left over at OpCo would then just flow through to HoldCo given that HoldCo owns the equity of OpCo. So, the unsecured notes at HoldCo would receive a recovery of fifty cents on the dollar.

If an upstream guarantee is put in place, things get a bit more interesting. The first question we would need to answer is what kind of claim the upstream guarantee confers to the HoldCo unsecured notes at the OpCo level.

While guarantees can be structured in a myriad of different ways – including being issued on a senior secured basis – you’ll most often see them (especially for interview purposes) providing HoldCo debt with a general unsecured claim at the OpCo level.

So, if the upstream guarantee provides HoldCo creditors with a general unsecured claim at the OpCo level then this would make the HoldCo and OpCo unsecured notes pari. Thus, we have $400 in debt, $300 in assets, and a recovery for both tranches of seventy-five cents on the dollar ($300 in distributable value divided by the $400 of pari debt).

If we change up our example a bit and say that the OpCo debt is now secured by the assets residing at OpCo while this upstream guarantee is still in place, then our outcome changes again. While this upstream guarantee will provide HoldCo creditors with a general unsecured claim at the OpCo level, it won’t change the reality that the OpCo secured debt is still ahead of it in priority at the OpCo-level. So, in this case OpCo creditors would receive full recovery and HoldCo creditors would, once again, receive fifty cents on the dollar. Thus, making them no better off, in this scenario, than if they had no guarantee at all.

Ultimately, corporate structures can become incredibly complex and verge on the point of being internally inconsistent. Part of the reason why the little narrative in the prior section revolved around a hypothetical offshore drilling company is that they are notorious for having difficult corporate structures to get your arms around. This is due to the breadth of geographies they operate across, which comes along with legal and tax issues, in conjunction with the desire to segregate assets so that they can maintain maximum flexibility to raise incremental debt when needed.

Take a look at Valaris’ corporate structure below. They had $7.1b of debt when they filed their Restructuring Support Agreement although, to be fair, their capital structure itself was actually reasonably straightforward with almost everything being issued out of the parent-level HoldCo.

So, in the real-world dealing with guarantees is really an exercise in scavenging credit docs and disentangling who is doing the guaranteeing, what benefit its conferring, and then determining what a given tranches overall priority really is.

Note: To avoid repetition, we'll just go through this one extended example here. There's quite a few more examples in the structural subordination post and many more in the guide in the members area (including some questions with more than two entities involved -- although those never come in interviews, I just created them to help build your intuition).

What is a Downstream Guarantee?

As you’d expect, downstream guarantees are just the inverse of upstream guarantees. Instead of the guarantee being extended from the subsidiary-level to the parent-level, the guarantee is being extended from the parent-level down to the subsidiary-level.

Or, in other words, instead of the guarantee being extended from the OpCo to the benefit of the HoldCo, the guarantee is being extended from the HoldCo to the benefit of the OpCo.

Now based on the little example in the prior section, a downstream guarantee from the HoldCo to the benefit of the OpCo wouldn’t provide any benefit (since the only value at the HoldCo will be whatever OpCo equity value exists – so we’re getting a bit recursive!).

However, in more sprawling real-world capital structures value from many different subsidiaries will be flowing up to the parent-level HoldCo and the HoldCo itself may have some assets of its own. For example, Transocean Ltd. is the parent holding company of Transocean and all of the secured notes – that are issued at separate rig-level operating companies – include guarantees from Transocean Ltd.

So, it’s entirely common and useful for guarantees to be extended by the parent to debt issued out of an operating company. For example, getting back to Valaris plc (the parent HoldCo) during the First Day Declaration, the following was said about notes issued out of Ensco International Incorporated, “ENSCO International Incorporated is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Valaris plc, and Valaris plc is the full and unconditional guarantor of the Ensco International Notes. All guarantees issued under the Ensco International Notes are unsecured obligations of Valaris plc ranking equal in right of payment with all of Valaris plc’s existing and future unsecured and unsubordinated indebtedness.”

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has been helpful. With my increasingly busy schedule over the past few months, I haven’t had as much time to write as I’ve been hoping for. However, I’ve been dealing with a number of complex corporate structures with lots of guarantees flying around, so I figured I’d write this more conceptual post covering upstream and downstream guarantees. Although, to be clear, you don't need to know all of the details in this post for interview purposes at all.

I also wanted to write this post to hit home, once again, the importance of looking at how things are defined and the need to always read the underlying credit docs -- because what you think things ought to mean is often quite different than what they really mean.

If you haven’t already, you should read the structural subordination post that covers more practical interview-style questions involving HoldCo/OpCo structures that have guarantees involved. There are also the classic restructuring interview questions and, if you’re just getting started, the restructuring investment banking primer that may be helpful to read through.